In 1990, African-American scholar Kobena Mercer wrote his infamous essay "Black Art and the Burden of Representation." And in it, Mercer identified a problem: that the art world expects black artists make work about an "essential black identity or experience." A key figure in addressing this problem, Thelma Golden—the director and chief curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem —supported a theoretical turn towards "Post-Black Art" (a response to Mercer's diagnoses), associated with artists like Glenn Ligon , Carrie Mae Weems , David Hammons , and Lorna Simpson . These artists challenged notions of essentialism, were "adamant about not being labeled 'black' artists," and posed complex questions about what it means to bring "blackness" into visibility.

In this interview excerpted from Phaidon's Contemporary Artist series book Lorna Simpson , Golden probes Simpson on the challenges of representing the female black body, and pushes her to confront her complex (and not completely amicable) relationship to feminism. (Want to see Simpson's work in New York? Make sure to check out the re-installation of Simpson's seminal piece Hypothetical? from the 1993 Whitney Biennial at the Fisher Landau Center for Art in Long Island City, on view until August 7th.)

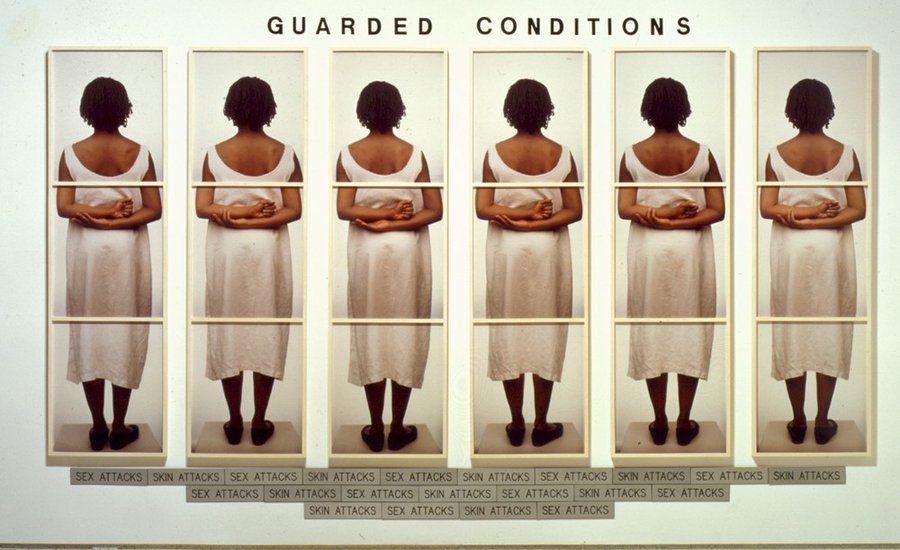

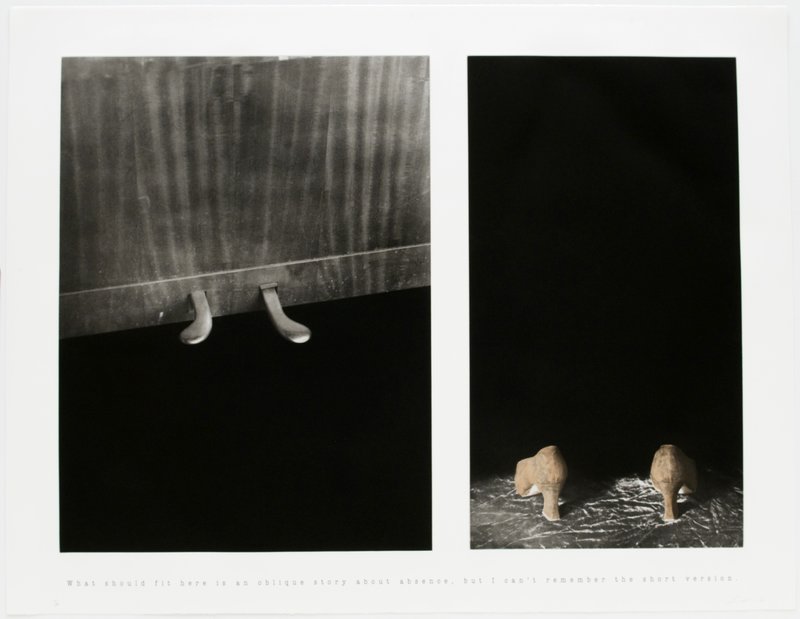

Lorna Simpson,

Easy for Who to Say,

1989

Lorna Simpson,

Easy for Who to Say,

1989

It seems to me that your move away from the body [in the late 1980s and early 1990s] had something to do with the way in which your work was in many ways responsible for a whole dialogue opening up around issues of representation, around the body, around the figure, around gender, around race. What else informed your decision to move away from the body, which was such a part of your work?

There was a feeling of discomfort that the audience immediately recognizes the way that the work operates and has a particular expectation of what they're going to see. The whole premise of the work was to engage with the audience in a way they wouldn't be used to—to put them off balance. It comes to the point when the audience, if they've see it enough and heard or read enough about it, already know the dynamic you've set up and then they don't so much figure out but assume how particular pieces operate. And that for me is not an interesting relationship between my artwork and the viewer.

Another reason that's much more personal is that during that time my mother died, many friends had died of AIDS, and there seemed to be an overwhelming feeling of absence. Even emotionally it seemed appropriate that the figure was absent. The death of a parent or friend also transforms you in a way that makes it difficult to return to the things you did before. That's why there was an abrupt switch away from it—not because I'm uninterested in terms of the subject, and not because I thought that I didn't have anything more to say, or that there was no audience for what I was saying, but purely in terms of process and my own personal feelings.

Lorna Simpson's sculpture

III (wish)

(1994) is available on Artspace for $1,000

Lorna Simpson's sculpture

III (wish)

(1994) is available on Artspace for $1,000

But in the way that you used the body, specifically a black woman's body, there was an absenting as well, because you never revealed the faces of your models. In some ways you already have absence, which is the stark difference from your film work, where you engage these models, actresses, the people in your films as presences, and you allow them to exist with their own faces, bodies and personalities. There was a lot of conversation about your work at that time about this denial, which some people never quite understood. Or they misread it, because without a face it assumed a certain autobiographical quality that made it always a picture of you.

I don't think it is me!

And so that body seems problematic on so many levels: absented, confused, misidentified, misread...Now, your work embraces bodies. How would you categorize that transition?

I see both areas as working with artifice. If I have a model, or a surrogate, a performative individual in front of the camera for a still photo, I'm trying to question the viewer's engagement with portraiture. When they experience a representation of a particular individual, what information do they think they're geting? I see working with actors in the films in the same way, because what they're giving is artifice; this is not them as individuals. The older works were photographed in a studio that was set up; I requested them to perform stories and to be particular characters, or they could form the characters themselves. Both types of works are about artifice—no one is who they actually appear to be. There is no autobiographical subjecthood or biographical subjecthood in terms of the people who are performing in the films.

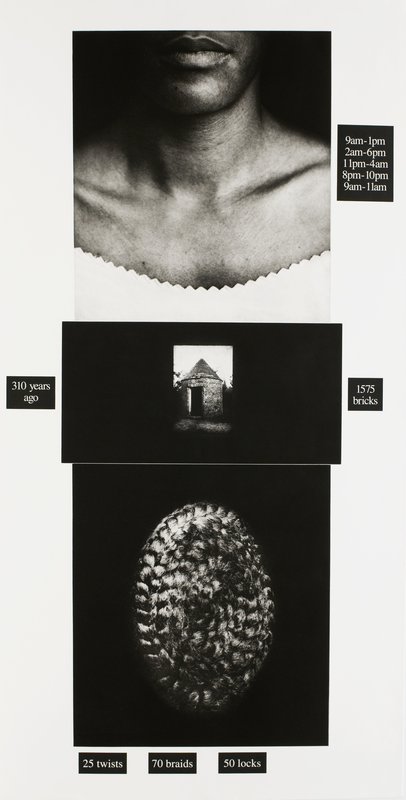

Lorna Simpson's photograph

Counting

(1991) is available on Artspace for $8,000

Lorna Simpson's photograph

Counting

(1991) is available on Artspace for $8,000

But what's interesting is that in the early photographs, the subjects with their faces obscured were read simply through gender and race. They were read totally generically either as you, or as some kind of prototypical, hypothetical, archetypal black woman. The characters in your films now, though of all races, are read outside of that. They're not performing as an archetype.

No they're not. But because I still use black-haired, Latin American, Indian or Eastern people—they're Brazilian or Chinese, or Korean, or African-American or African—a lot of attention is still paid to race. If you look at the works from the 1980s and early 1990s of black women, and then at the film projects, there's an equal level of response, in that these characters aren't seen as a kind of stepping-off point towards a universalism. They're generically seen as black characters or as people of ethnic groups. Whatever the subject of my work, it will always first be categorized in those terms. I have my own utopian sense that at a certain point people's relationship to this work will change, that it will not come to the forefront as "Oh, they're black!"

It's not a racialized reading that you're bringing to your own narratives?

No. But the way that they're interpreted out in the world—they're racialized first. Regardless of whether I'd shown the face or not in those photographs from the 1980s, or if an actor performed a particular character in a film piece fifteen years later, all this baggage about race becomes an interpreter by which your work gets read.

Lorna Simpson,

C-Rations

, 1991

Lorna Simpson,

C-Rations

, 1991

Let’s say a little bit about your newer work,

Untitled (impedimenta)

(2001). There’s always been a subtle rebuke, through the insistent presence of bodies of color in your work, of their absence in art history. And this last body of work takes this to another level.

Lorna Simpson, Detail of

Untitled (impedimenta)

, 2001

Lorna Simpson, Detail of

Untitled (impedimenta)

, 2001

The body of work contains oval and square images, and they’re all of a woman’s head, slightly out of focus. There’s a little bit of her revealed, but not much; we kind of see her face, but the photographs lie just beneath a translucent material and become silhouettes or are clouded or glossed, so you can only just make her out. The references within the work are titled of paintings from the 1790s to about 1970, and of films from about 1910 to the 1970s. Formally, the ovals point to turn-of-the-century photographs and daguerreotypes—photographs that people would carry around, images of their loved ones. The four-by-five, rectangular images represent modern photography and art. I mix those up in a kind of incomplete grid, so that it’s somewhat fallen apart and not completely filled in, but the grid structures each individual piece.

My first idea was to create a piece in which I had a character who goes through the same motions over a 100-year period. I was looking for a narrative that could be repeated every thirty years by a different character, and would shift and change over the course of decades, given the nature of the address of that period and their context of the time in which the narrative was spoken. That became a little too complicated and I didn’t like the way it worked out. I realized that the titles of paintings revealed their context over the course of time, and also defined a particular historical moment—like a portrait of a slave in the nineteenth century. But even the images from the late 1970s, which have a completely different political position in terms of representation, are revealing of the way they describe themselves. In all the paintings and all the films there is no consistent ethnic group or person in terms of authorship. What is depicted within those paintings or films is the presence of Africans or African-Americans who are either in the background or at the forefront. What interested me about the titles that I chose was that they seemed highly loaded and spoke very much about time in terms of their language and their address, and also the way they saw in their subject, or the invisibility of the subject.

Each of these works that you selected has a black figure in it. You look at this as an expansive scan across history, recording the presence or absence of the black figure—it's sort of a personal look at that presence-absence. How do you feel about making work in which the presence of the black body is consistently foregrounded?

Given the generation that I was brought up in, and given the way in which that affects how I see things now, I cannot take that presence for granted. The moment I take that presence for granted the dominant image will quickly return to a kind of monolithic, non-ethnic depiction. That irritates me on a day-to-day level. This is not to say there aren't any black images in circulation, particularly in film and painting; fields have opened up and there's a lot more black work to see. I just don't take any of it for granted.

The way in which you position these works is not necessarily about the past, but about the constant fight for visibility either in art or in film in the present.

It’s and off-shoot that is forgotten or put aside or that is still struggling to bear a sense of importance and place within the canon.

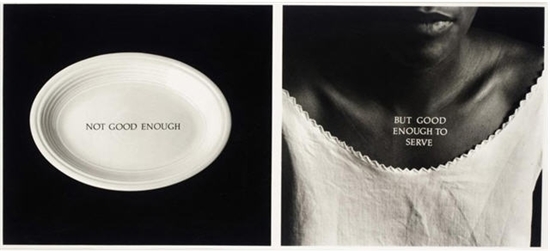

Lorna Simpson,

Same

, 1991

Lorna Simpson,

Same

, 1991

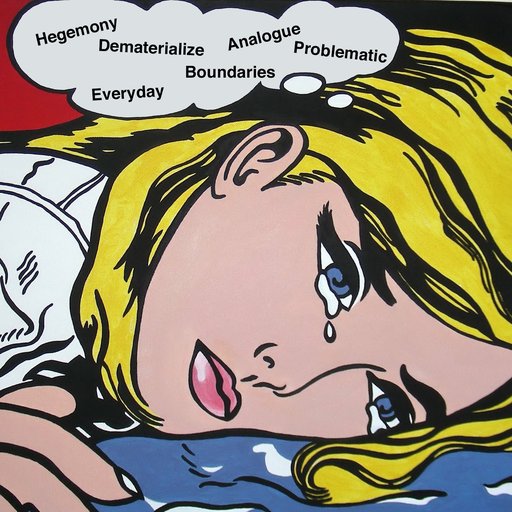

Where do you see your work existing in the lineage of feminist-inspired contemporary art?

The work was embraced by feminist writers and academics, and is to this day.

Was that something that was comfortable or uncomfortable to you?

Part of my inability to answer these sorts of questions is because there was a fracture within feminism in the late 1970s in terms of the involvement of women of color. In the past ten or fifteen years there’s also been a kind of revisionist take on feminism by young women about what exactly it means as a political tool or position, which has further complicated the debate. Women’s reproductive lives, their autonomy, are probably the central most important aspects of feminism to me, personally, but over the past few years it’s kind of shifted. While in a certain sense my work operates within a feminist critique, it’s about negotiating and taking aspects from it that I feel are valuable. But I am not at the centre of a feminist argument.

But your work has been critically positioned within the feminist dialogue as resolving the issues around woman and women of color and women’s bodies in the lineage that includes work by Carolee Schneeman or Eleanor Antin . A whole realm of women created work that performed on, in and around women’s bodies and critique a notion of artmaking as an exclusive, masculine-dominated, patriarchal arena. It’s impossible now to enter into any course on women’s art and not get to 1985 and have Lorna Simpson’s work put forward as this almost religious pairing of race and gender. I’m asking you about how you feel about that; I see that there could be a certain ambivalence for you about that positioning.

When you make a work and that work becomes embraced, regardless of who it’s embraced by, and it’s used intellectually to support a particular agenda, it provokes a level of discomfort. I’m never in one place consistently; there isn’t a clear ideology that I’m trying to present, that’s monolithic or that’s so consistent it speaks to a particular gender.

Lorna Simpson's print

Untitled

(1993) is available on Artspace for $1,250

Lorna Simpson's print

Untitled

(1993) is available on Artspace for $1,250

Your work has consistently used women’s bodies, almost exclusively. Did feminist work influence you in this choice?

I think maybe that choice was made more from reading literature. What came out of feminism originally was a kind of gay or lesbian agenda. Notions of feminism do run throughout my work in terms of the body and control, but a lot comes from literature.

In looking back and thinking about the work and how it's developed, where do you see it going now?

I see my work as revisiting photography. It's a difficult relationship to return to; I haven't worked with photography for so long, yet it's still very familiar.